Key Activities for Building Internal Products

An article in which I take alliteration to a potentially obnoxious extreme by explaining product development activities with 7D's and 2C's.

In the last 2024 issue of InsideProduct, I mentioned that I planned to write more about this in 2025:

I figured the best place to start is to explain what this is, and then from there launch into a series of posts looking at each “D” in more detail (as well as a couple of “C’s” that I realized that I need to incorporate somewhere.

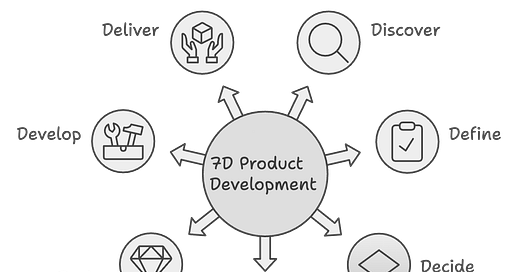

The 7D’s of Product Development

This particular graphic came about as I looked for a way to organize the various topics related to working on internal products.

I wanted to organize topics in terms of the activities that product teams do when working on internal products and explicitly not create a framework, lifecycle, or methodology.

We have enough of those, and I find that frameworks, lifecycles and methodologies have a major issue that prevents them from being extremely helpful for folks who just want to get things done. I’ll explain more on that later.

So to set the stage for future issues, here’s a brief description of each of the 7D’s - my attempt to categorize the activities that a product team does to build, maintain, or configure internal products.

It’s worth noting that these activities do not happen in specific phases. They’ll occur (at varying intervals) throughout the course of the time you’re working on an internal product.

Discover your users and their needs

Discovery means taking steps to understand who use (users) or are impacted by (stakeholders) your product and their needs.

For internal products, users and stakeholders will generally be employees in your organization, but may also be people outside your organization involved in delivering the product or service your internal product supports.

You’re trying to understand what these folks are trying to accomplish, and the environment in which they’re trying to accomplish it. It’s those specifics that often get associated with the generic term “needs”.

The activities I’ll typically include under the category of discovery include interviews, observing processes, and analyzing data from existing internal products.

Define the problem to solve

Define means to clearly explain the need you’re trying to satisfy or problem you’re trying to solve without explicitly stating a solution.

I chose to split this out as a set of activities because it’s crucial to effectively creating or maintaining an internal product and it’s a step that rarely occurs. That’s because most teams in an internal setting find themselves getting handed solutions to deliver, without much explanation as to why.

An example of a couple activities that get categorized under define is formulating a problem statement or performing an opportunity assessment.

Make decisions all along the way

Decide means to pick a specific direction from a set of options. It’s what you should do every time you come to a figurative fork in the road.

It’s worth splitting this off as a separate set of activities, because product teams face decisions at different levels every day, and the success or failure of product efforts often comes down to whether and how a product team makes those decisions.

Describe the solution

Describe the solution covers all the activities you take to ensure a shared understanding of the way you’re going to solve a particular problem.

Based on what I see happening in practice, this is where I’d classify most of the activity around requirements including PRD’s, user stories, process flows, data models, and business rules.

I also chose to separate this from design the experience because I think each set warrants it’s own category because they look at the solution from different perspectives.

Design the experience

Design the experience means putting careful forethought to how users will interact with the solution.

I chose the word experience intentionally because there’s often more to a user’s interaction with a product than just the product itself.

And it’s worth noting this is one of the areas that’s often neglected in internal products, unless the product has customer facing aspects.

Develop the solution

Develop the solution means building a new solution, making revisions to an existing solution, or configuring an off the shelf solution.

Alongside describing the solution, this is the point where most product teams who work on internal products are most familiar, again because they’re usually handed a solution to bring to the world.

I’m including both building (in the case of custom built software) and configuring (in the case of off the shelf or SaaS) because you’re accomplishing the same thing in either case. I also group any testing and QA activities here because they should naturally be a part of that same activity, and I couldn’t think of a testing related word that started with a D.

Deliver the solution to users

Deliver the solution means providing the product to the people who are going to use it and preparing them to use it effectively.

That second part is key and it’s incorporation in practice seems to be haphazard at best. I also chose to split out develop and deliver because each set of activities warrants special attention.

Two C’s to add in

As you read through those above descriptions, you may have thought some key points were missing, such as who does these activities and when are you supposed to do them.

I left that information out on purpose because determining those things is not nearly as straight forward as a lot of people would have you believe.

It’s also why I realized that in order for the descriptions of the 7 D’s above to be helpful, you need a couple of C’s to go along with them them.

So I’m adding in these additional concepts that I’ll also write about, and will ponder how to best incorporate them in to the graphic.

Collaborate to make it happen

Collaborate to make it happens means a group of people working together to perform all the activities listed above.

Developing internal products is a team sport. As shown by the 7D’s there are a variety of different activities that require different skills to complete them successfully. Any product team you form is going to need to have someone that has each of those skills.

I’m not saying that one person has to have all those skills, nor am I suggesting that it should be a one to one relationship between skill and person.

While I’d like to have a team that has all the skills somewhere, I don’t want that to result in a product team that becomes to unwieldy.

So trying to identify a specific role that’s going to do each activity is a fools errand. Each team will have different people with different mixes of skills. The activities that do count are each team figuring out who will do what in their particular situation.

I also include activities surrounding how the people on that product team work together and with stakeholders outside their team in this category.

Consider context to figure out what, who, and how

Considering context means understanding the unique characteristics of the organization, the problem to solve, and the product team to figure out what activities your product team needs to perform when and also how you’ll go about doing it.

Remember earlier when I mentioned the big flaw that frameworks, lifecycles, and methodologies have? They usually don’t take context into account. Rather, some budding thought leader experiences a certain situation where a collection of activities worked really well together for a particular effort. They reason that if worked for me, it could work for others, and I can make a boatload selling certifications about it.

The problem is there were probably unique characteristics of the situation where they tried it that don’t carry over to other situations.

So my intent when covering context is to give you some tips on how to read the room and figure out what may and may not work in your situation.

Thanks for reading

Thanks again for reading InsideProduct.

If you have any comments or questions about the newsletter, or there’s anything you’d like me to cover, let me know.

Talk to you next time,

Kent