Explaining discovery for internal products

My attempt to explain what discovery looks like for internal products, starting with a look at product discovery.

In a previous issue of InsideProduct, I shared the key points from our ProductTank Des Moines/Ames discussion about product discovery.

Many of the ideas discussed were applicable to products in general, but mostly assumed products that an organization sells to people outside the organization.

In this issue of InsideProduct, I thought it was about time to talk about discovery explicitly in the internal product context.

Is discovery common in internal products?

While discovery is viewed as a critical product management activity, people working on internal products may not think they regularly perform discovery. At least the type of discovery you typically hear product managers talk about: product discovery.

As I worked on this article, I kept going back and forth between whether I should refer to discovery or product discovery. I figured I should probably determine if there is a useful difference. So, in the interest of time, I posed the question to Perplexity. (I’m not above using AI for the proper use cases, research on potentially pedantic topics being one of them).

The general gist is: Discovery is uncovering new information, opportunities or insights. product discovery is determining what to build by validating solutions against customer needs, feasibility, and business goals.

So product discovery is a particular type of discovery for a specific purpose. I’ll use both terms and have these definitions in mind when I use them.

There’s a few reasons they may give.

First, people working on internal products are more likely to to be handed a solution to deliver, so there isn’t the perceived need to perform any kind of product discovery in the first place.

Second, an organization’s customers may not directly interact with many internal products. As a result product people assume that it’s not as important to understand customers and their needs.

Third, teams working on internal products are often measured based on their output. They don’t feel like they can take time away from delivering features to do research.

I said there were reasons. I didn’t say they were good reasons.

What is product discovery?

Turns out you may do more product discovery than you realize, and there’s always room for more.

It may be helpful to describe what folks in the product management world mean when they talk about product discovery.

For that, I’ll reference Marty Cagan in Inspired How to Create Tech Products Customers Love. In that book he explains the purpose of product discovery two ways. Fortunately, they support each other.

Product teams need to learn fast, yet also release with confidence The purpose of product discovery is to:

make sure we have some evidence that when we ask the engineers to build a production-quality product, it won’t be a wasted effort.

address these critical risks with evidence: Will people choose to use it (Value risk); Can the user figure out how to use it (Usability risk); Can we build it (Feasibility risk); Does this solution work for our business? (Viability risk); Should we build it (Ethics risk)

It’s also helpful to reference Teresa Torres’ simplified contrast of product discovery and product delivery:

Product discovery is deciding what to build. Product delivery is building it

Problem space and solution space

It’s also common to note that product discovery happens in two “spaces”.

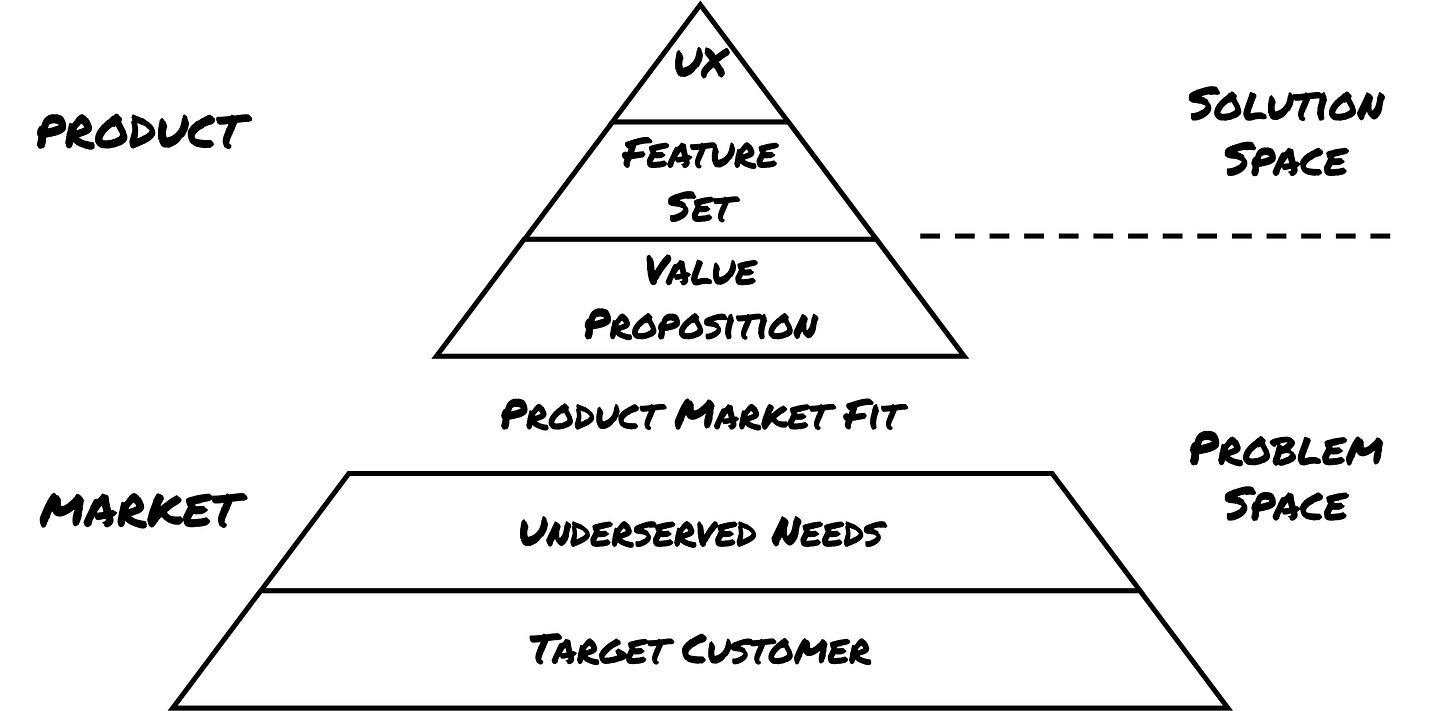

In the Lean Product Playbook. Dan Olsen refers to the problem space and the solution space.

problem space is where all the customer needs that you’d like your product to deliver live. solution space includes any product or representation of a product that is used by or intended for use by a customer

Teresa Torres has the same concept, but replaces the word “problem” with “opportunity”:

Good product discovery requires discovering opportunities as well as discovering solutions.

I’m going to stick with “problem” because “problem to solve” seems to roll of the tongue ( or keyboard) easier.

Product discovery in practice

To describe all that in more practical terms, a product team working on a tech product uncovers information in order to determine what problem to solve. A common activity (but certainly not the only one) is interviewing potential customers to understand their needs.

Then, the product team needs to uncover information to identify solutions to solve that problem, and determine the most suitable one to build. This involves activities such as showing users prototypes and testing assumptions.

So what about discovery for internal products?

With all that in mind, let’s talk about how this relates to internal products.

Discovery in the problem space

Most teams working on internal products are handed a solution to deliver. Something along the lines of “rebuild this 20 year old app built in Power Builder”, or “I need a report.”

This is what I refer to as a solution looking for a problem.

You could take this request at face value and start eliciting requirements.

Or, you could spend a little time in the problem space and do a bit of discovery to understand your target users and their underlying problem.

In the case of “I need a report” this would look like sitting down with the person requesting said report and asking them about the time they determined they needed a report. Ask them to tell you a story. Ask for lots of details.

You may use questions such as:

What were you trying to accomplish?

What information were you missing?

What did you do since you didn’t have that information?

These are more helpful, and less confrontational ways to ask “why?”

In terms of the 7D’s, you’re doing discovery to work back from the given solution so you can define the problem.

Discovery in the solution space

Then once you know the problem you’re trying to solve, you can now uncover information to identify potential solutions and pick the most appropriate one.

Again, for those business analysts out there, “requirements elicitation” probably popped into your head. And it turns out that the most effective activities for discovery in the solution space are common elicitation techniques. Hence one of the reasons I suggest that skilled business analysts are well positioned for product management in an internal product setting.

In practice this looks like “discovering” the business processes, rules, and data you need to care for in your solution.

In terms of the 7D’s, you’re doing discovery in order to best describe the solution you decide to develop and deliver.

So why label this discovery instead of just using requirements elicitation? There are some perspectives and techniques that business analysts can learn from product managers and vice versa. So I think it’s helpful to call out differing names for similar activities. Frankly, I don’t care what you call it.

It’s more productive to get exposure to those different perspectives and techniques and learn how to apply them to your situation then arguing about what you call the approach you use. At the end of the day, people trying to get real work done could care less what it’s called.

When do you do discovery for Internal Products

Ideally, you’ll want to spend some time doing discovery in both the problem space and the solution space.

You probably experience more impact from problem space because it may help you avoid doing work you don’t need to do. Discovery applied right helps you avoid trying to solve problems that aren’t really problems or don’t make sense for your organization to solve.

By it’s very nature discovery in the problem space happens at the beginning of an effort. As an example, here’s how I used discovery sessions to get started on an effort in response to a request to “rebuild this 20 year old app built in Power Builder.”

Discovery in the solution space is something you do continuously. It results from a gradual understanding of the problem through building a solution, or getting feedback on existing product or first part that you roll out.

Discovery is ongoing because as you build aspects of the solution, you’ll want to do more in depth discovery into the aspect of the solution you’re working on. That means don’t expect to get all the details figured out too early. It’s actually not that helpful.

If you’re doing backlog refinement properly, you’re incorporating discovery in the solution space alongside building increments of your solution.

Your discovery stories

Hopefully that description of discovery in internal products was helpful. There’s a lot more involved, which I plan to go into more detail on in future issues.

To help me know which aspects I should focus on, please let me know your questions, or topics in the realm of discovery you’d like a deeper dive on.

Thanks for reading

Thanks again for reading InsideProduct.

If you have any comments or questions about the newsletter, or there’s anything you’d like me to cover, let me know.

Talk to you next time,

Kent